If you’ve been working a while, you’ve probably had more than one corporate déjà vu moment. Maybe it’s a group dynamic gone sideways or a CEO’s self-inflicted wound. They leave you head-scratching about why, despite all the MBAs and consultants (guilty of being both!), we keep ending up in the same pickles.

This year I decided to step back and take a broader look at organizational dynamics, to see whether their intricacies broadly weave into a few patterns. I reached out to the modal edges of my network. Ok, still mostly MBAs and consultants, but all with 20-45 years of cross-industry work experience, ranging from small to multinational and from startup to mature companies. While current roles skewed towards tech, experience spanned civil engineering and international development, venture capital and law, with titles ranging from manager to Vice President.

I asked these wise business leaders at the zeniths of their careers to look back on their collective experience and consider the same three questions: “What are mistakes you see happen in organizations over and over again? What is causing them? What can you do to change the pattern?”

What emerged isn’t just a simple list, distilled from 22 perspectives. Certainly there are meta themes. But what stood out more was how every interview felt both individual and systemic at the same time. Each deep diagnosis framed not just the endemic challenges each leader was squaring up to, but also what values they held and aimed to deliver. On the whole, when individual choices meet organizational evolution, certain ‘mistakes’ will manifest like clockwork.

Organizational growing pains: some ‘mistakes’ are inevitable

Sitting down with a seasoned engineer who’d experienced every size and maturity of business, I received a stoical reframing of my premise: There are no mistakes. “Mistakes” we observe are not made in error. Rather, they are “structural artifacts” of an organization’s current stage of growth and maturity. If you group all companies into three simple buckets, here’s what you can expect.

- 🐣 Small businesses: These entrepreneurs are building the plane while flying it. They make mistakes out of sheer inexperience, learning the “nuts and bolts” because there’s no one else to do the work.

- 📈 Rapid growth companies: Welcome to the competitive wild west. You need to scale up to meet demand, but then keep outdoing yourself to stay profitable. Rapid growth, chasing the next innovation can be messy. Reaching new levels of scale that require new leadership expertise can also drive churn, contributing to the chaos.

- 🧓 Large, stable companies: These behemoths are set in their ways, sporting policies and procedures for every scenario, having seen it all over decades. While this might feel like “boring” adulting, it’s how they operate globally at scale. But it’s also how you fall asleep at the wheel and become irrelevant.

Basically, a company making “mistakes” might just be living its truth. And that might bump up against your own goals, values, or preferences.

Of course, these company maturity categories are artificially clean and binary. And the magnitude and frequency of “mistakes” can still vary significantly. One can certainly take the rough with the smooth, but also try to temper the rough patches. So let’s have a walk through the topics that popped across interviews. What are the most common — let’s call them problems — and how might we remedy them?

🎶 I got 99 problems but grouped them into 4

The following short list is by no means exhaustive. Consider it the 80/20 of org “watch-outs.”

Group 1: People problems

Most common: Bad hiring, bad management

Typical culprits: Small businesses, rapid growth companies

Typical causes: Inexperience, time pressure

| “Founders are really bad at hiring. They tend to hire someone for roles they are bad at. It’s hard to hire someone for something you don’t know how to do.” – Venture Capital Investor “I previously worked with [recruiting] during an aggressive expansion. The company was thinking about the ideal way to hire, number of interviews, what you can learn. One issue is hiring incorrectly. It has a profound and long-lasting impact. They stay long and bring on other people who aren’t right too.” – Senior Director, large tech company |

The take-aways

1. Invest in hiring and onboarding

“I valued [my former company’s] time, thought, and structure put into hiring decisions. And it’s a standardized process that helps compare candidates…The moment you let people do their own thing, it’s impossible to hire well.” – Senior Director, large tech company

“Most people don’t think about how to make the person confident and competent in the role. And then check in with that person and give feedback.” – Vice President, mid-sized tech company

2. Expect managers to enable talent at every level

“[Direct reports] need direction, guidance, coaching, mentoring, apprenticeship. But they don’t need to be micromanaged…You should let them unleash their talent.” – Partner, top global consulting firm

“57% of people have left a job because of a manager. People should take more stock of the people issues vs. just speed.” – Career coach and Founder

“A lot of people hire someone external without creating an environment for success, and it takes too long for them to figure out how to get things done. New hires don’t have enough internal authority to push things through. A sponsor should enforce metrics around the change they want.” – Senior Strategy Manager, large tech company

Group 2: Focus problems

Most common: Unclear mandates, high reactivity

Typical culprits: Rapid growth companies; large, stable companies

Typical causes: Market pressures, catering to leadership, high novelty or complexity

| “I see a lot of reactive solutions. Something gets shrill, the geist of the moment. e.g. change of administrations, AI. There’s nothing wrong with reacting. Sometimes we move too fast to come up with something brand new, and we over-react. And [reactive solutions are] not built for longevity.” – Head of Strategy & Operations, large tech company “R&R is a challenge [in my function]. It’s unclear who the owner and who the decision-maker is. By default you think it’s the highest ranking person, but that’s not always the case. Otherwise you just keep having working sessions. – Product Strategy and Operations Executive, large tech company |

The take-aways

1. Ensure top-down clarity on strategic direction

“The order of decision-making should be strategy, organization, people; not people, organization, strategy…A lot of times people propose org changes that are solving for people. Or you see you’re working around the strategy.” – Vice President, large tech company

“[All companies need] a clear, well written plan. This includes strategy, mission, vision. There’s also the outcomes you want to measure to know if you’re successful. Some companies don’t have one or both. Some have both but are poorly written and executed. Lots of people don’t include what they won’t do. Companies do poorly at setting goals and [conveying] why they matter.” – Director, large tech company

2. Be targeted and deliberate in assigning shared ownership

“If everyone’s doing the same thing it’s not clear what you’re driving. There are areas that it would be really powerful to have shared goals. But in other places we can move faster as separate units. We [need to be] intentional about when we take approach A vs. B.” – Director, large tech company

“People tend to focus on their area of responsibility over how that area of responsibility affects something bigger. They focus on in-quarter metrics over long-term trends… [But big-picture thinking is] fundamental to maintaining the health of the business…In part it’s a question of empowering individuals. In part it’s signalling to people that that’s how they should be operating.” – Managing Director, large tech company

Group 3: Process problems

Most common: Slow decision-making, limited accountability

Typical culprits: Large, stable companies

Typical causes: Org complexity

| “The way our orgs are designed, with [multiple functional leads] all reporting to different people means there are too many decision-makers… The advantage is a higher degree of excellence…[but the tradeoff] is multiple layers of direction and [dispersed] accountability.” – Senior Product Leader, large tech company “[Different divisions] have different motivations… There are too many goals to be aligned.” – Senior Software Engineer, large tech company |

The take-aways

1. Match the process to the objective and risk

“We see a lot of one-way door decisions. That affects the speed we can tackle problems. Many one-way door decisions are expensive to change or impact brand reputation if you make the wrong call. We could move much faster if we identified decisions [with] two-way doors, with fewer executive reviews and alignment [needed]…You can simply identify ‘what decisions could I reverse today?’…People reviewing work set the tone, including giving coaching [on what they] don’t need to review.” – Senior Product Leader, large tech company

“Centralization vs. decentralization: When do you want to focus on consistency, speed, and execution (centralization), using top-down mandates vs. when do you want people to figure it out and do it their own way, since you don’t know the right way, and eventually make it consistent…Make that decision consciously.” – Strategy & Operations Executive, large tech company

2. Set R&Rs and accountability frameworks

“We have a very matrixed organization. It’s not clear who’s on the hook… It’s a structural challenge. You’ll get people in the room that weigh in that aren’t accountable, so shouldn’t be an extra opinion. That’s most large companies. That causes slowness. [Correcting for this] has to be intentional by top leadership. They have to regularly check in that it’s the right structure to achieve their goals.” – Director, large tech company

“In the kickoff meeting, we don’t set up a decision-maker, they just say we’re all working on it. You see a meeting with a dozen [approvals] required. We need to be more explicit. We need a leader to… assert [R&Rs and] ownership. The owner then has to tell people who’s doing what…It comes back to ownership.” – Strategy & Operations Executive, large tech company

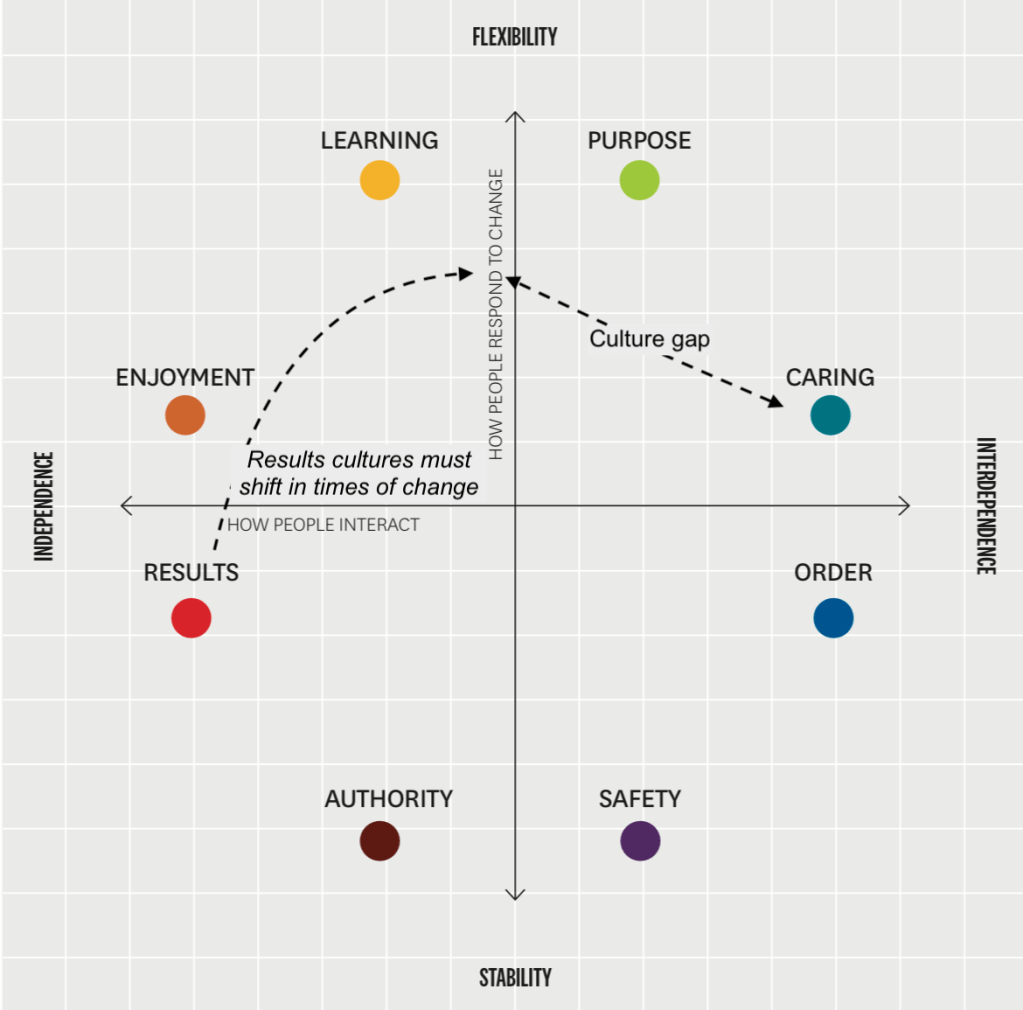

Group 4: Culture problems

Most common: Low psych safety, siloed communication

Typical culprits: Rapid growth companies; Large, stable companies

Typical causes: Loss aversion, deified leadership

| “A mistake I see made a lot is people playing pretend. Not acknowledging reality, pretending things are good when they are not.” – Technical Professional Services Head, large tech company “[People have a] perception of leadership that they have all the answers.” – Founding Partner, impact investing startup “Any time the team grows, there’s a breakdown in communication. Every time you shift to no longer being in the room together, comms shift. There’s angst around hierarchy, around process and suddenly needing it.” – Career coach and Founder |

The take-aways

1. Model imperfection and risk-taking

“Everyone in the chain has to feel their leadership is supportive. If one person feels safe but the next stop up doesn’t feel safe, it won’t work. People need to see examples to believe it. Leadership has to model how they’ve made mistakes and asked for and received leadership support. There needs to be a way to reward and highlight the behavior.” – Director, large tech company

“In early stage companies they explore, but when you hit a certain size, it’s too difficult to allow freedom, because that introduces risk. And risk appetite goes down with time…Find the members of leadership that are incrementally more open than the rest, and push them to find creativity. Use that as a test case to prove. It’s an incremental approach.” – Founding Partner, impact investing startup

2. Normalize open communication and collaborative feedback

“The Achilles heel for orgs is an inability to distinguish between accountability and blame. Accountability is an opportunity to look at something that isn’t working and try to figure out how to problem-solve together…. Vs. blame. That creates an environment where people are unwilling to identify problems.” – Director, large tech company

“People are more agreeable in group settings to give a sense of niceness and organizational cohesion. This is the root of many problems. Having backbone and being willing to disagree is important for organizational health, so people feel like they can raise important concerns… [I have seen] people disagree in backchannels or silent discontent. Then you miss the perspectives of people. [We need to] create a safe space where people feel they can vocalize opinions… You can say why you don’t agree with it, offer data, ask for more input from that person.” – Senior Product Leader, large tech company

Final notes: Expect the expected

The above org problems are less about individual human fallibility and more about the inherent design, stage of development, and maturity curve of the organization itself. Among the four problem groupings, each org type has their “favorites”. Rapid growth companies have more people problems due to hiring at a rapid clip. Large, stable companies have more process challenges due to system complexity and risk aversion. All can suffer from communication breakdowns.

So if you are experiencing corporate déjà vu, you’re not crazy. You’ve seen this movie before. It’s a classic plot, and still worth a watch. But don’t just get out your popcorn – this is a choose-your-own-adventure. Know thyself, and choose which org type you want to be in.

And if you are in an org that you feel is missing the mark, I’ll leave you with one last inspirational quote:

“I think people believe some problems are too big for them to fix. Then they focus on the controllable. But there are instances where you’ve got to step beyond that, and take responsibility for difficult issues. It is a form of risk aversion to say that’s beyond what I can tackle. There needs to be a balance between what you can control and tackling the [big] issues.” – Managing Director, large tech company

Sometimes, it may be worth being bold and pushing for change. Either way, wherever you are, be the most adaptable, resilient ‘you’ you can be. As Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson would say, “Bloom where you’re planted.”