As a former innovation consultant, who designed initiatives, competitions, and recommended approaches for diverse clients, I was intrigued to hear that decision science scholar Sheena Iyengar, famous for her “jam study”, was now teaching, writing, and advising on innovation. I, of course, wanted to compare notes. Iyengar asserts that there are no new ideas, only new combinations of old ideas. True to her word, her methodology combines tried and true methods.

The Think Bigger Methodology

In Think Bigger: How to Innovate, Iyengar proposes a practical, six-step method to generate innovative solutions:

- Choose the [right] problem. Start by focusing on the problem, not the solution. Defining the right problem is a goldilocks challenge: to yield impactful, innovative results, you need a problem that balances specificity with broad enough relevance.

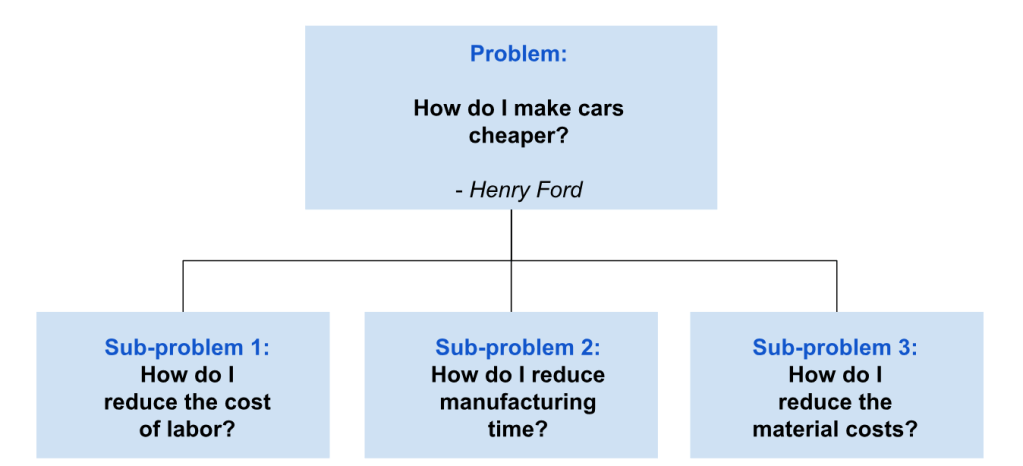

- Break down the problem. Address each component of the problem separately; this will enable combinatory options in Step 5.

3. Consider desires. Identify the motivations and desires of those impacted by the problem — including you, the innovative problem-solver; the target beneficiary; and third party stakeholders.

4. Search existing solutions. Learn from past attempts to address the problem; identify both failures to avoid and insights to use.

5. Create a “Choice Map”. Consider different combinations of wide-ranging solutions to the sub-problems. Select several full solutions to investigate further.

6. Seek validation: Get feedback on targeted aspects of your candidate solutions from others.

Iyengar’s key advice

In addition to simplifying the innovation process, Iyengar also strives to debunk common misconceptions. To increase efficacy, she advises targeting your efforts as follows:

- Get over shiny new object syndrome. The most unusual ideas are rarely perceived as more innovative. Instead, new applications and combinations of old ideas often get the most traction.

- Listen to your gut before you listen to the data. Ideas are a dime a dozen. But motivation is finite. Notice the direction of travel of your enthusiasm. Is it trending up, down, or flat as you refine your idea? This “real talk” will help eliminate magical thinking about your level of commitment. You need to feel passion to power through the process successfully.

- Spend more time researching solution options than you think you should. In contrast to the Lean Startup paradigm, which now dominates Silicon Valley and recommends racing to a minimum viable product, Iyengar recommends spending more time researching many possible MVP options.

- Don’t ask for feedback on the full solution. People are likely to judge your idea before its fully-baked. To effectively refine your concept, ask for selective, narrow feedback on specific aspects you are testing.

Nothing new under the sun

Iyengar arrives at core principles consistent with what I’ve seen work. Essentially, she is an advocate of open innovation and lateral thinking — problem-solving by looking beyond traditional organizational or social boundaries and connecting seemingly outside ideas. Given how tried and true her methodology is, I wondered why she chose to write the book. Iyengar herself highlights that even her Choice Map is largely derived from the GE Trotter Matrix.

I believe Iyengar wrote Think Bigger for three reasons: 1) she believes everyone can be innovative and, thus, sought to create an empowering “user manual” of sorts, 2) she observed common pitfalls among her students that she wants to help others avoid, and 3) she’s an academic — she must publish or perish.

To the first motivation, I agree that anyone can be innovative if they look outside their disciplinary or professional silo. This is part of what drew me to study Public Policy as an undergraduate student — it combines a basket of disciplines oriented around solving a challenging problem: designing rules for society. Political Science, Philosophy, Economics and other disciplines can not take on this challenge single-handedly. But while I agree that solutions to complex problems need to come from outside a single silo, I do not think a solopreneur or small team can crack the code as easily as Iyengar implies.

By optimizing her solution identification process for a single person, Iyengar’s methodology is both empowering and overpromising. Think Bigger reads as if one person can transform a product category, industry — nay, the world! — with little more than a worksheet. Yes, it’s a handy worksheet, and with time a single person can run the research process of identifying promising solutions to the target problem. But this individualistic approach limits output to that of one person / team vs. incentivizing many solvers to tackle the challenge — which is the core of a true open innovation approach.

To the second motivation, Iyengar’s advice certainly can save time and help individuals learn from others’ mistakes. As a decision-psychologist, she is versed in the mental tricks our own minds play on us. However, Iyengar’s own biases color her advice. As a full-time academic, she over-indexes on research, suggesting conducting enough research to produce thousands of potential solution combinations. Acknowledging this overwhelming option set, Iyengar then suggests selecting test solutions using a random number generator. How odd to recommend a big upfront investment, followed by an arbitrary narrowing-down process. Perhaps this is where the third motivation — to publish due to peer-pressure — may be tainting her recommendations as well.

Iyengar closes by reasserting, there are no new ideas, just different combinations of old ideas. This claim sums her book up well. She steels with pride and references, offering handy tools that can spur focused creativity. But they are not quite the cure-all implied.