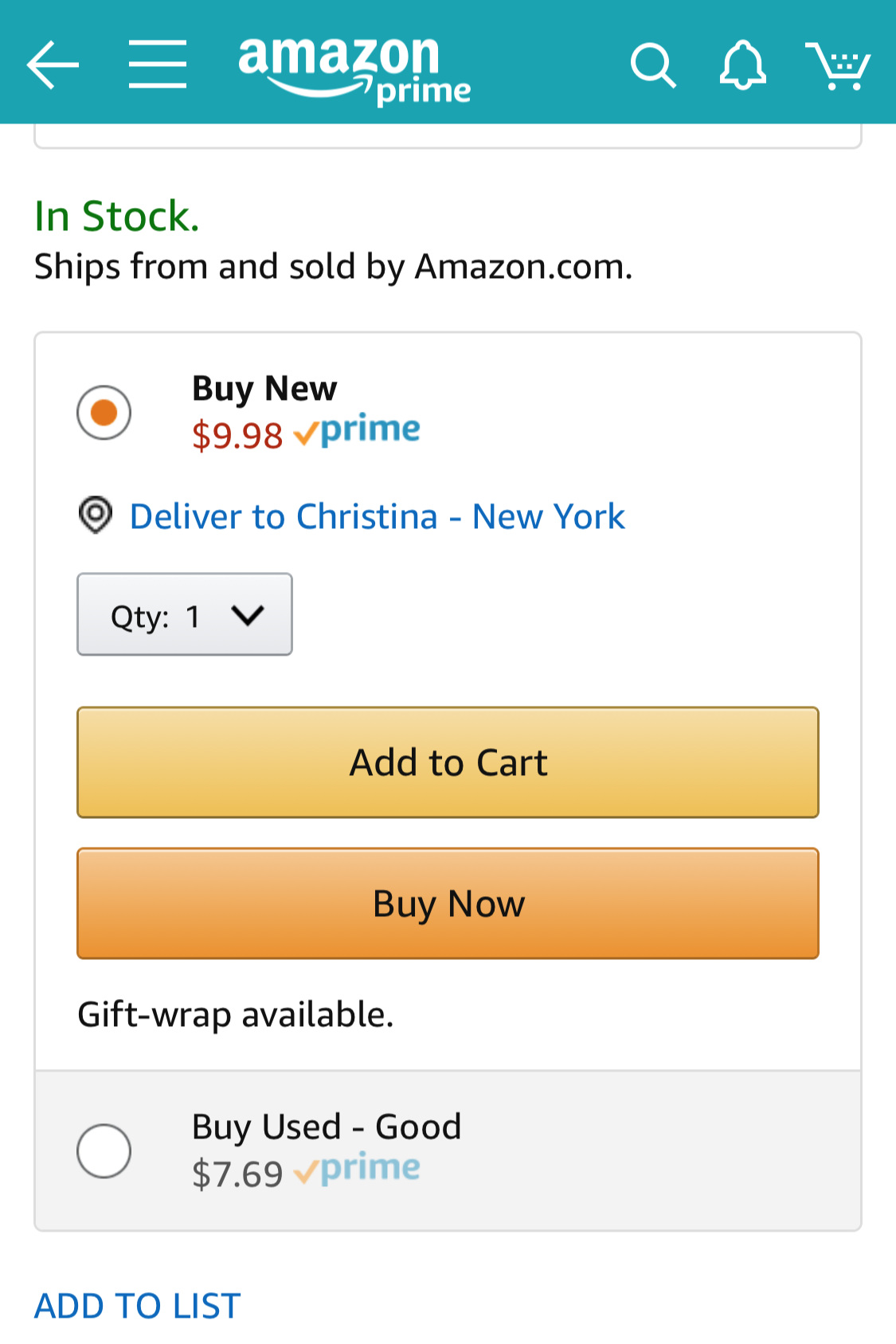

From Intuit to Amazon, dark patterns have emerged as an inescapable part of our our digital lives. A dark pattern, as Fast Company succinctly put it, is “a user interface that has been carefully crafted to trick users into doing things.” And it’s different to bad UI. It’s the inviting blue button on TurboTax that leads you to a paid tax return form, next to a garish orange button that leads you to the free filing option. It’s the greyed-out, less expensive option on Amazon below the default selected, more expensive Prime option. In short, the default is the annoying thing.

Given the ubiquitous presence of dark patterns, consumers seem to be waking up and wondering “how did we get here?” Taking that question one step further, are there any redeeming qualities of dark patterns? And if not, what should we do about their rampant use?

How we got here

Dark patterns are largely the product of the capitalistic pursuit of money and the commodification of people’s attention. And we can probably thank the ruling doctrine of the day, the Lean Startup method, for this newfound efficiency of capturing money and attention. Lean Startup methodology asks a fundamental question of product engineers: when we make changes to a product, how do we know we’ve made it better? Lean Startup devised a means of fast learning about product efficacy through rapid testing. And Intuit, the owner of TurboTax, was the poster child featured in the book. Fast-forward a decade later after Eric Ries has transformed the speed of learning at Intuit, and they have deployed their newfound abilities to guide consumers to costly decisions: TurboTax ripped off troops with a bait-and-switch dark pattern promising a “Military Discount” and milked the unemployed with a misdirection dark pattern, obscuring the free filing option with obtuse language, convoluted website pathways, and wiping the free page from search results.

Is it all that bad?

Intuit’s CEO fought back against the media bashing to say that their dark patterns were in the “best interest of taxpayers”. Many dark pattern architects might argue the same thing. Take the example of newsletters. Almost every online vendor has made newsletter subscription an “opt out” option at checkout, with “subscribe to our newsletter” checked as the default. Such vendors might posit that they want to deliver useful deals and information that you just don’t know you want or need yet. You can all but imagine the disembodied sales bot saying, “it’s not a trick, it’s a legitimate sales tactic in the best interest of the consumer.”

There are a few rare instances where dark patterns are motivated by consumer service priorities. For example, some cloud providers will provide a default option of using the regional data center with the most capacity, rather than the data center you most recently used. Most customers choose the default, and receive more reliable service as a result.

But for the most part, dark patterns are the evil twins of nudges. A nudge is “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives”. Think putting fruit at eye-level and candy on the bottom shelf. Or how the Austrian government makes organ donor the default status for citizens, resulting in over 90% donor status vs the US’s ~15%. The UK government loved the concept so much that they created a “Nudge Unit”, more formally known as the Behavioral Insights Team, to influence public policy.

Are dark patterns just nefarious nudges? Not exactly. The big difference between nudging and dark patterns is in the definition. Dark patterns, by definition, “trick consumers” to do something they wouldn’t want to do. It’s not simply that you make one option more top of mind; it’s making the desired option appear to be the only option, to the benefit of a private company, over the consumer body.

What’s a consumer to do?

Regulation is one possible solution to dark patterns. The Federal Trade Commission and local Consumer Protection Offices already protect against a number of aggressive and fraudulent sales tactics. If you’re in Europe, GDPR may be helping consumers out too. However, with today’s gridlock in Congress, we may be on our own as consumers for a time. But we do have our own power of the purse. So vote with your dollars! If you notice a company using dark patterns, don’t reward them with your patronage. Companies are using dark patterns because they work. If we show them that they don’t, then they won’t. Preference vendors who don’t use dark patterns.

Lastly, in researching this piece, ProPublica, who provided the deep dive on Intuits abuses of consumers, hit me with their own dark pattern.